My recent tweet about the fascination with the dividend or investing only in companies that pay it is not entirely wise drew some mild disapproval. In this article, I'd like to elaborate on this topic.

Link to tweet 👇

https://twitter.com/horacekpetr22/status/1651842115951788033

What are dividends anyway?

Dividends are the profits companies pay out to their shareholders. Companies can share them on a regular basis - quarterly, semi-annually or, as is common in the Czech Republic, annually. From time to time, it is also possible to come across special dividends where companies pay out a certain amount of money, for example because they have accumulated it through normal operations and have no use for it, or when they may receive money for the sale of one of their divisions.

It's still important to remember that dividends, even though they are effectively a share of the company's profits, should always be covered by free cash flow, because just because a company generates a profit on the books doesn't mean it actually has enough money in the bank.

Why it is good if a company pays a dividend and what it brings us besides money

"The only thing that makes me happy is to see dividends coming in."

John D. Rockefeller

We all like the feeling of "no money in the bank". It shows us that we could be financially independent and if enough money comes in that way, we don't have to go to work.

There are a number of people who actually do and live off a combination of bond interest and dividend payments. Kudos to them!

Dividends also serve as a diversification of current income for many and psychologically help them because they know that if they lose one source of income, they have another.

In tough times in the markets, dividends can provide the means to buy stocks at lower prices and make us feel like we are at least getting something out of our investments.

This is also linked to the fact that stocks that we still 'get something out of' are psychologically better to hold for longer periods of time.

Are dividends really what we should be looking for?

Let's first look at why companies actually pay a dividend and then look at the purpose of the investment and what we can take from it as investors.

If a company generates a profit, it has several options for what to do with it. Below are ranked from the best ones.

- Reinvest in your own business - if the company you are investing in, for example, operates a fast food chain, it can use the profits to open a new branch or expand existing ones to make them more efficient. It may be that further investment "in itself" is no longer feasible or does not bring sufficient return, then other alternatives come in.

- Acquisition of other companies - another way to handle profits is to buy other companies. This is generally riskier, as management may make a mistake and misjudge the assets being bought, or may not be able to merge them under one company. There are, however, companies that specialise in "serial acquisitions" and, thanks to them, have grown into true giants. Examples are Constellation Software or Berkshire Hathaway.

- Buybacks - publicly traded companies always have a certain amount of shares outstanding that represent a stake in the company. If management deems it appropriate (ideally, because it considers the shares undervalued relative to the value of the company), it may decide to initiate what is known as a buyback. In practice, this means that it will start buying its own shares from the market, thereby 'cancelling' them. The other shareholders will thus be entitled to a larger share of the profits. Let's imagine that a company has 100 shares and earns $10. That means earnings per share of $0.10. However, if it buys back 15 shares, the remaining shareholders already get $0.117. In practice, this should be reflected in a higher share price as its EPS (earnings per share) rises. The advantage of buybacks is that they are subject to a 1% tax (applicable to US-based companies) and until last year were not taxed at all (on the company side).

- Dividends - if a company has no way to invest in its growth, can't buy anyone out, or its stock is expensive, the last option is to pay out a share of the profits, i.e. dividends. Generally speaking, most companies that pay out most of their profits in this form are already at the end of their road. This is not necessarily a bad thing if they are adequately priced and will be able to pay out money for a long time to come. The problem is that companies that have a high dividend yield often face various problems and their dividend payout may not be sustainable because of this.

What is the point of investing?

The purpose of an investment should generally be, taking into account the risk, to maximise the value of the amount invested.

I am deliberately omitting here the need to generate cash flow from it, as this can be achieved in the stock market by gradual divestment, which is even likely to be more tax-efficient (dividends are taxed at 15% here, whereas divestment at a profit is tax-free after 3 years).

The total return on investment is then made up of 3 parts:

Growth in share value + dividends paid + spin-offs received (doesn't happen often, that's why I don't include it in the example).

In practice, this means that if I bought a stock for $100, it appreciated in value over ten years to $223, while paying a dividend of $5 each year, I am $165.5 richer at the end, or 165.5%.

The original $100 is $223, so +$123, plus ten years of dividends of $5 each is $50, but I have to take 15% tax out of that, which means I only have $42.5 in my account.

42,5 + 123 = 165,5.

Why did the stock go from $100 to $223?

There could be two reasons for this, the first being the rise in valuation. Suppose the company earns $10 in earnings, so it trades at a P/E of 10. If its valuation rose to a P/E of 22.3, then at the same EPS the stock price would be just $223.

The second, more likely scenario (also the one we'll work with in our example) is that the company's profits have risen, here instead of $10 the company earns $22.3, at the same valuation this again means a share price of $223.

What if the firm reinvested the profits instead of paying a dividend?

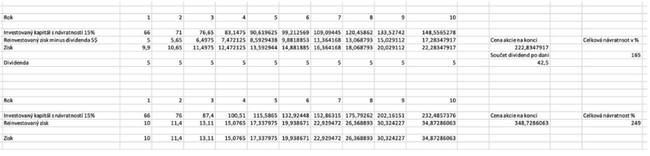

Our example assumes that the firm pays out $5 in fixed annual dividends. In the figure below, we can see a comparison of what it would look like if it reinvested all of its earnings instead, and what our return would look like if, in both cases, such a firm traded at 10 times its earnings 10 years from now.

The attached table shows that if a firm has a ROIC (Return on Invested Capital) of 15% and has $66 in invested capital in the first year, it earns $10, which means it is trading at a P/E of 10 for $100. The firm also pays a fixed dividend of $5, while reinvesting the rest of the profits, so our return will be 165% over 10 years. Which is more than respectable.

But let's imagine that instead of a $5 dividend, the firm reinvests those earnings with the same return into its business. So in 10 years, it won't be earning $23, but $34. Which, at the same P/E, means that at the end we can sell it for $348 instead of $223. That's $125 more expensive, and even after dividends, our return will be 249%, which is 84% higher.

Ask yourself, which stock would you rather invest in? Would you trade a few dollars of cash each year for a substantially better return?

What's the takeaway?

As investors, we should be primarily interested in the total return that an investment will bring us. Dividends in and of themselves are neither bad nor good. There are companies where it is desirable to pay them, and then there are companies where it would be downright bad.

At the same time, from an investment perspective, we need to look not only at how the company we want to invest in is doing, but also at what price we are buying it. Looking only at companies that pay dividends, or preferring them, shrinks the investment universe and makes no sense from a capital allocation perspective.

In fact, companies that pay out most of their profits have limited opportunities to reinvest them in themselves, which means that their profits either grow very slowly or not at all. In practice, this usually translates into their share price not moving much or even falling, and investors can at most console themselves with the dividend they receive.

Invest with caution.

Please note that this is not financial advice.